Fig.1 Schematic diagram of the proposed

Abstract Avibration energy harvester can harvest vibration energy in the environment and convert it into electrical energy to power the sensors in the Internet of Things. Human walking contains high-quality vibration energy, which serves as the energy source for vibration energy harvesters due to its abundant availability, high energy conversion efficiency, and environmental friendliness. It is difficult to harvest human walking vibration due to its low frequency. Converting the low-frequency vibration of human walking into high-frequency vibration has attracted attention. In previous studies, vibration energy harvesters typically increase frequency by raising excitation frequency or inducing free vibration. When walking frequency changes, the up-frequency method of raising the excitation frequency changes the voltage frequency, resulting in the best load resistance change and reducing the output power. The up-frequency method of inducing free vibration does not increase the external excitation frequency, which has relatively low output power.

This paper designs a magnetostrictive vibration energy harvester with a rotating up-frequency structure. It consists of a rotating up-frequency structure, a magnetostrictive structure, coils, and bias magnets. The main body of the rotating up-frequency structure comprises a torsion bar and a flywheel with a dumbbell-shaped hole. The magnetostrictive structure includes four magnetostrictive metal sheets spliced by Galfenol and steel sheets. The torsion bar and flywheel interact to convert low-frequency linear vibration into rotating high-frequency excitation vibration of the flywheel. The flywheel plucks the magnetostrictive metal sheet with a high excitation frequency to generate free vibration. The vibration energy harvester increases the excitation frequency while inducing free vibration, which can effectively improve the output power. To characterize the excitation vibration and free vibration, based on the theory of Euler-Bernoulli beam theory, the vibration equation of the magnetostrictive metal sheet after being excited is given. According to the classical machine-magnetic coupling model and the Jiles-Atherton physical model, the relationship between stress and magnetization strength is derived. Combined with Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction, the distributed dynamic output voltage model is established. This model can predict the output voltage at different excitation frequencies. Based on this model, the mechanical-magnetic structural parameter optimization design is carried out. The parameters of the magnetostrictive metal sheet, the bias magnet, and the rotating up-frequency structure are determined. A comprehensive experimental system is established to test the device. The peak-to-peak voltage and output voltage signal by the proposed model are compared. The average relative deviation of the peak-to-peak voltage and the output voltage signal is 4.9% and 8.2%, respectively. The experimental results show that the output power is proportional to the excitation frequency. The optimum load resistance is always 800 W as the excitation frequency changes, simplifying the impedance-matching process. The maximum peak-to-peak voltage of the device is 58.60 V, the maximum root mean square (RMS) voltage is 9.53 V, and the maximum RMS power is 56.20 mW.

The magnetostrictive vibration energy harvester with a rotating up-frequency structure solves the problem of impedance matching, which improves the output power. The proposed distributed dynamic output voltage model can effectively predict the output characteristics. This study can provide structural and theoretical guidance for up-frequency structure vibration energy harvesters for human walking vibration.

Keywords: Vibration energy harvester, magnetostrictive,rotating up-frequency, dynamic model, free vibration

With the continuous development of internet of things (IoT) technology, connecting everything has become a reality. There are many sensor nodes in the IoT[1-2], which require high reliability and need to be online for a long time. Solving the problem of powering sensors is a pivotal task[3-4]. Until now, most of sensors have been powered by batteries, which have life cycle issues and require regular maintenance or replacement[5]. It has become a difficult problem to ensure the long-term stable operation of the sensor. The process of human walking contains high-quality vibration energy, which is widely distributed in the human living environment. Therefore, vibration energy harvesters that harvest human walking vibrations are proposed as an alternative to sensor batteries[6-8].

The vibration of human walking is low- frequency vibration. Low-frequency vibrations are difficult to be effectively collected and utilized. Therefore, converting the low-frequency vibration of human walking into high-frequency vibration has attracted the attention of researchers. Based on electromagnetic induction, piezoelectricity and mag- netostriction, researchers have designed vibration energy harvesters with various up-frequency structures to harvest vibration energy of human walking. These vibration energy harvesters can be divided into two types: on-body type and off-body type, according to the installation position. The on-body vibration energy harvester refers to a harvester installed on the human foot. Qinxue Tan etc[9]. proposed an electro- magnetic vibration energy harvester with a cantilever- driven rotor, which converts human walking vibration into rotation and generates a peak power of 1.8 mW. Ning Zhou etc[10]. proposed a stacked magnetic modulation electromagneticvibration energy harvester with frequency up-conversion, which can produce 7.9 mW RMS power when installed on the ankle. Zuozong Yin etc[11] proposed a shoe-mounted piezoelectric energy harvester, which uses the impact between the ratchet and the piezoelectric beam to increase the frequency. The RMS power of the device is 0.98 mW. Due to volume limitations, the output power of the above-mentioned on-body vibration energy harvesters are small. And the on-body vibration energy harvester interferes with the normal walking of the human body. These shortcomings limit the practical application of on-body vibration energy harvesters.

Off-body type vibration energy harvesters have no effect on the normal walking of the human body[12]. It has a high output power and strong expandability, and can power multiple sensors in the IoT simultaneously. Phosy Panthongsy etc[13] proposed a cantilever beam piezoelectric vibration energy harvester. The device consists of 24 piezoelectric cantilever units. When a foot is placed on the device, the deformation of the piezoelectric cantilever induces free vibrations, which in turn increases the vibration frequency. The RMS power of the device is 1.24 mW. Since the frequency of the voltage generated by free vibration remains constant, the optimal load resistance of the device is also constant. The advantage of such a design is that the power harvested from the energy harvester is always maximized regardless of changes in the walking frequency. The disadvantage is that the external excitation frequency received by the cantilever beam has not been increased, resulting in a relatively low output power of the device. Yisong Tan etc[14]. proposed a double-frequency up-conversion magnetostrictive energy harvester. The device con- verts the low-frequency vibration of walking into the high-frequency rotational vibration of a multi-leaf cam. The device increases the excitation frequency of the magnetostrictive sheet by 8.13 times, so its output power reaches 31.3 mW. The advantage of this design is that the excitation frequency of the magnetostrictive sheet can be increased, resulting in high output power. The disadvantage of this design is that when the walking frequency changes, the frequency of the voltage harvested by the device also changes, resulting in a change in the optimum load resistance, which reduces the power. Both of the above two methods of up-frequency have shortcomings which affect the output power of the vibration energy harvester.

A magnetostrictive vibration energy harvester with a rotating up-frequency structure is proposed, which can be used to harvest the vibration energy of human walking in public places. The device is composed of a rotating up-frequency structure, a magnetostrictive structure, coils and bias magnets. The rotating up- frequency structure can simultaneously induce excitation vibration and free vibration of the magnetostrictive structure. A distributed dynamic output voltage model of the energy harvester is established to describe the mechanical-magnetic-electrical coupling relationship. The model also provides a basis for the mechanical and magnetic structural parameter optimization design of the energy harvester. The output characteristics of the device are tested and discussed.

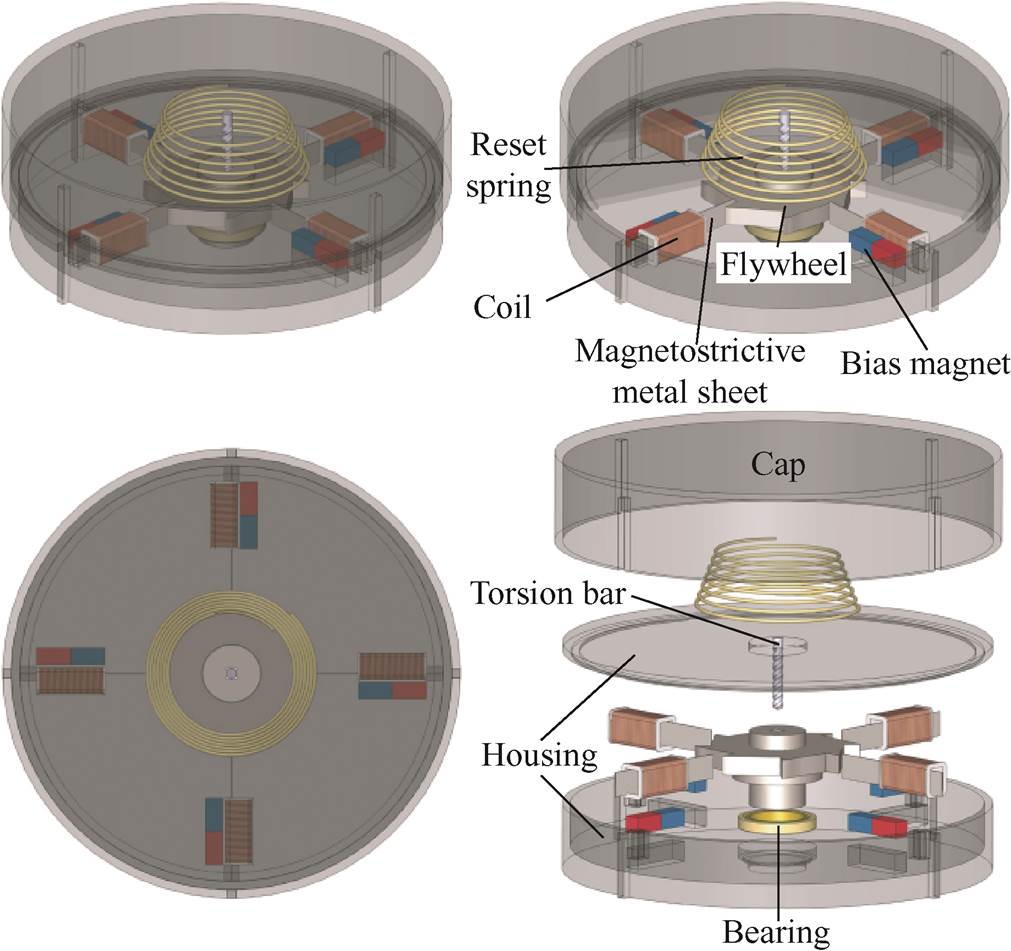

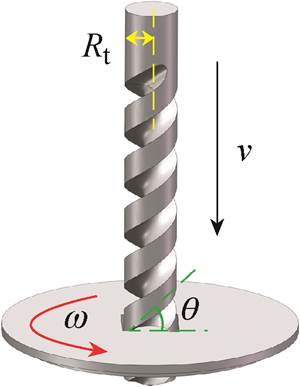

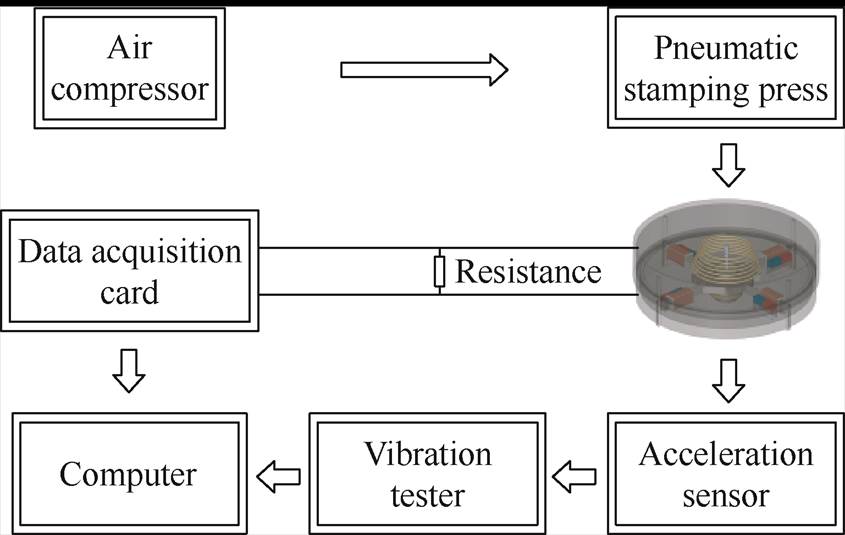

The schematic diagram of the rotating up- frequency structure magnetostrictive vibration energy harvester (UMVH) is shown in Fig.1. The device consists of a rotating up-frequency structure, a magnetostrictive structure, coils and bias magnets. The main body of the rotating up-frequency structure consists of a torsion bar and a flywheel with a dumbbell-shaped hole. The torsion bar and flywheel interact to convert low-frequency linear vibrations into rotating high-frequency excitation vibrations. The role of the bearing is to provide stable support for the structure, while the reset spring ensures that the depressed torsion bar can return to its original position. The magnetostrictive structure is composed of four magnetostrictive metal sheets, and its function is to convert the mechanical energy of vibration into changing magnetic energy. Through four coils connected in series, the magnetic energy is converted into electrical energy. The bias magnet provides a suitable bias magnetic field for the magnetostrictive metal sheet, and this suitable bias magnetic field can enhance the output voltage. Additionally, the housing and cap are 3D printed from cured resin.

Fig.1 Schematic diagram of the proposed

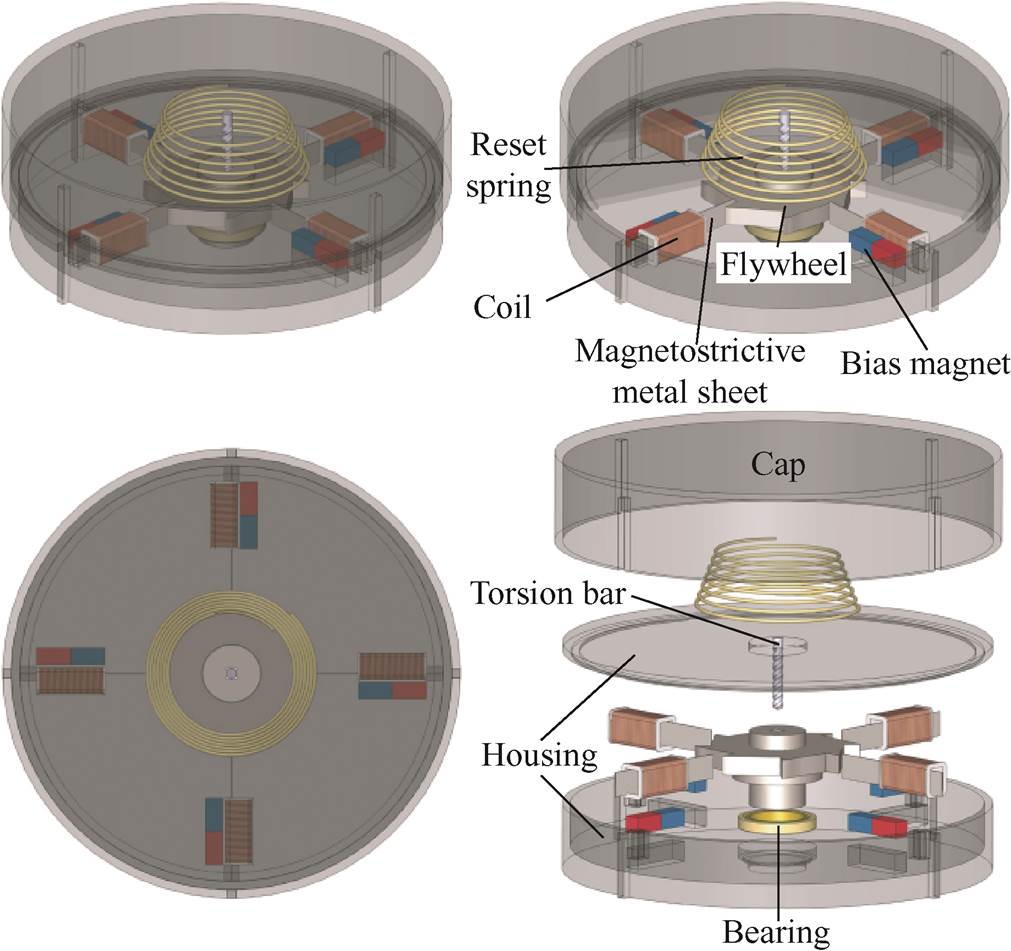

The vibration energy harvester is embedded in the ground of a public place. When a pedestrian step on the cap of the device, the cap is subjected to vertical downward pressure, which causes the torsion bar to move downward. As the torsion bar moves downward, it applies a tangential force to the dumbbell-shaped hole, causing the dumbbell-shaped hole to drive the pawl to rotate counterclockwise. Then the pawl and the ratchet mesh with each other, thereby driving the flywheel to rotate at a high speed. Fig.2a illustrates the schematic diagram of the interaction between the torsion bar and the flywheel during the downward process. The flywheel then interacts with the mag- netostrictive metal sheet. The interaction process can be divided into two stages. In the first stage, the flywheel plucks magnetostrictive metal sheet, and the magnetostrictive metal sheet generates excitation vibration, which converts the low-frequency vibration of human walking into high-frequency vibration of rotation. In the second stage, the flywheel leaves the magnetostrictive metal sheet, and the magnetostrictive metal sheet generates free vibration. In both stages, the magnetic domains inside the magnetostrictive material deflect due to stress changes resulting from free vibration. According to the Villari effect, the deflection of the magnetic domain will lead to the change of the magnetic field inside the coils. An induced voltage is generated on the coils in accordance with Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction. When the downward pressure is released, the reset spring drives the cap and torsion bar upward, returning the device to its original position. During the upward process, the torsion bar applies a tangential force to the dumbbell hole, causing it to rotate the pawl clockwise. When the pawl rotates, it compresses the spring and can only slide against the ratchet, thus causing the flywheel not to rotate. Fig.2b illustrates the schematic diagram of the interaction between the torsion bar and the flywheel during the upward process.

Fig.2 Schematic diagram of the interaction between torsion bar and flywheel

This device uses the coupling of the Villari effect and the Faraday's law of electromagnetic induction to harvest the vibration energy generated by human walking. By the rotating up-frequency structure, the excitation vibration frequency is increased and the free vibration of the magnetostrictive metal sheet is realized, thereby increasing the output power of the device.

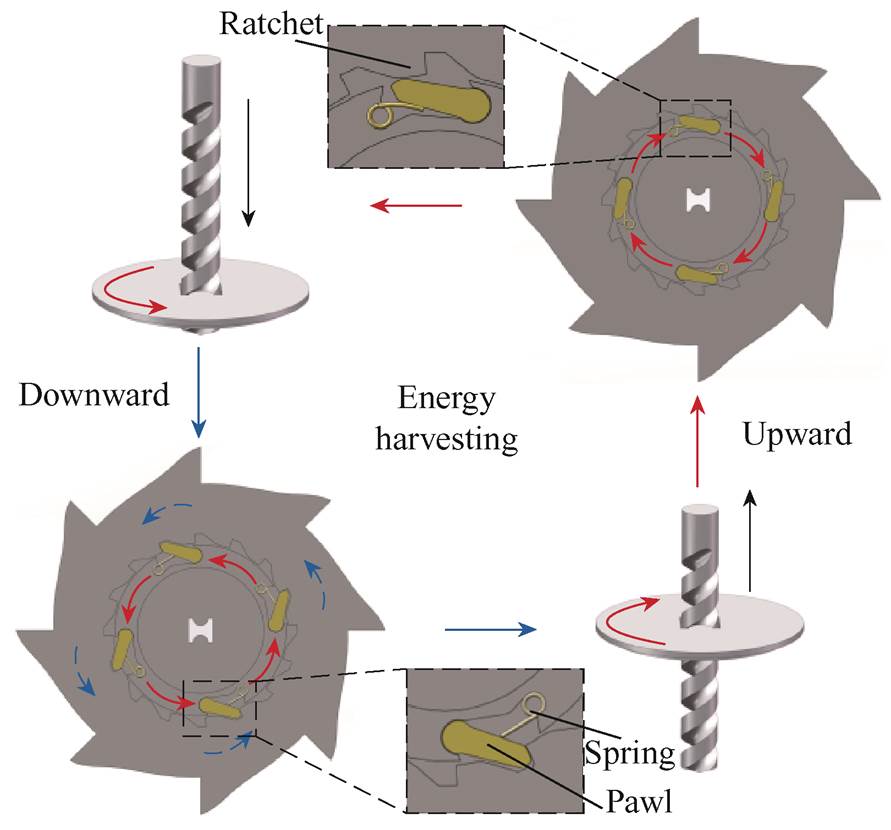

When a person steps on the cap of the device, the cap will obtain a downward velocity v, and drive the torsion bar to move downward together. Fig.3 illustrates the schematic diagram of velocity con- version for rotating up-frequencystructure, in which the downward motion is converted into the rotation of the flywheel. The angular velocity of the flywheel can be expressed as follows

(1)

(1)

where v is the velocity of downward pressure, Rt is the radius of the torsion bar, q is the thread angle of the torsion bar.

Fig.3 Schematic diagram of velocity conversion for rotating up-frequencystructure

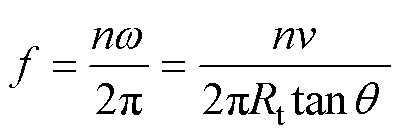

The excitation vibration frequency of the magnetostrictive metal sheet is called the excitation frequency. The magnitude of the excitation frequency is determined by the number of teeth (n) on the flywheel. Therefore, the excitation frequency of the device can be expressed as

(2)

(2)

The relationship between the magnetic field strength (H) inside the Galfenol sheet along the length axis and the magnetization strength (M) can be expressed as

(3)

(3)

where m is the magnetic permeability, m0is the vacuum permeability, Hi is the bias magnetic field in the Galfenol sheet.

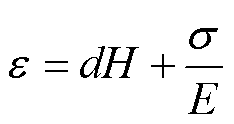

The linear piezomagnetic equation is used to describe the magnetostrictive inverse effect of Galfenol sheets.

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

where sand ε are the stress and strain of Galfenol sheet, respectively, dand d* are the piezomagnetic coefficients of Galfenol sheet, B is the magnetic flux density, E is the Young's modulus of Galfenol sheet.

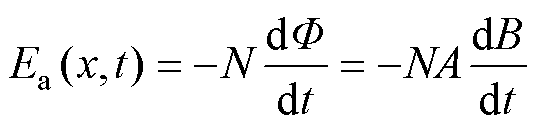

According to the Faraday's law of electro- magnetic induction, the induced electric potential in the coil can be expressed as

(6)

(6)

where F is the magnetic flux, N is the number of turns of the coil, A is the cross-sectional area of the coil.

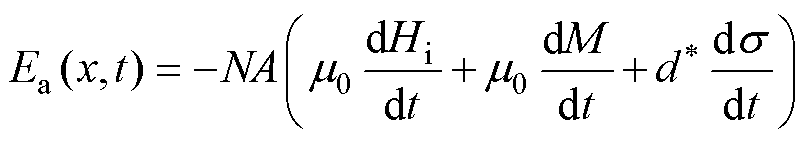

By incorporating Equ. (3) and Equ. (4) into Equ. (6), It can obtain the expression for the induced electric potential.

(7)

(7)

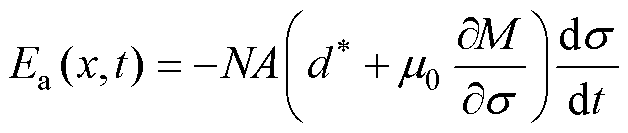

In this device, the bias condition is constant, and Hi is considered to be a constant. Equ. (7) can be simplified as

(8)

(8)

Equ. (8) reveals that the output voltage magnitude of the UMVH is influenced by both ∂M/∂s and ds/dt.

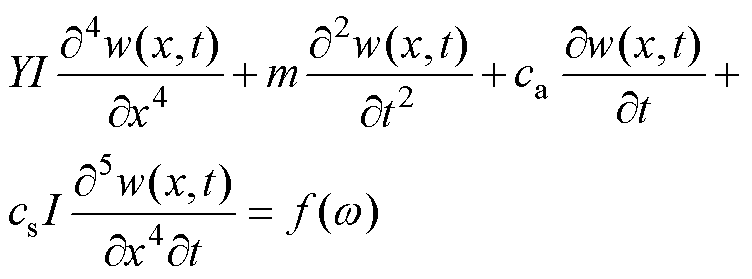

By combining the classical machine-magnetic coupling model with the Jiles-Atherton physical model[15], it is possible to deduce that

(9)

(9)

Where Ms denotes the saturation magnetization strength of the Galfenol sheet, a is the anhysteretic magnetization shape coefficient,  is the magnetic susceptibility,

is the magnetic susceptibility,  is the energy coupling coefficient perunit volume, c is the reversibility magnetization factor.

is the energy coupling coefficient perunit volume, c is the reversibility magnetization factor.

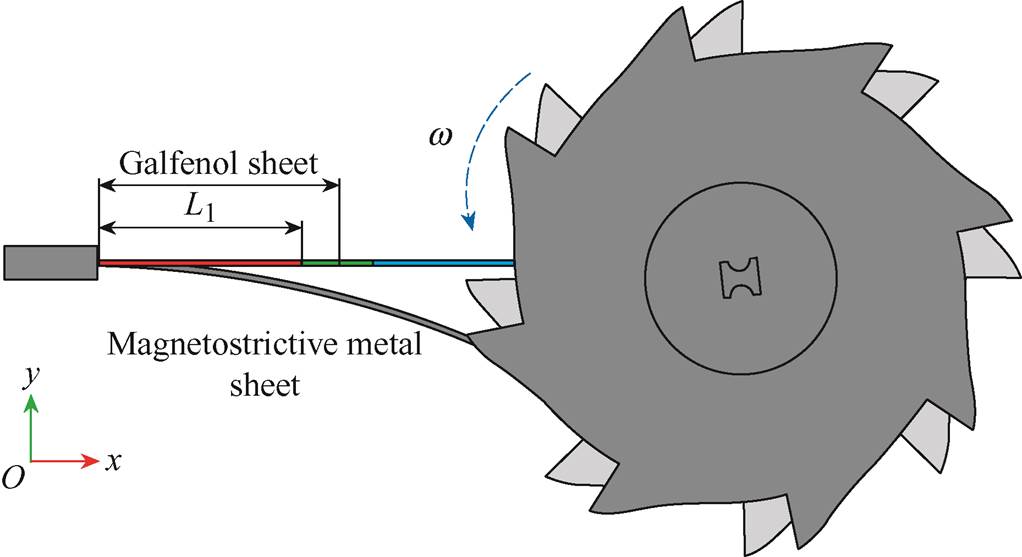

Fig.4 illustrates the equivalent schematic diagram of the interaction between the flywheel and the magnetostrictive metal sheet. L1 is the length of the portion of the Galfenol sheet wound with the coil.

Fig.4 The equivalent schematic diagram of the interaction between the flywheel and the magnetostrictive metal sheet

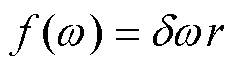

Based on the Euler-Bernoulli beam theory[16], the vibration equation of the magnetostrictive metal sheet can be described as

(10)

(10)

Where Y is the elastic modulus of the magnetostrictive metal sheet, I is the equivalent moment of inertia of the magnetostrictive metal sheet, w(x,t) is the deflection, m is the mass per unit length of the magnetostrictive metal sheet, cais the strain rate damping coefficient, csis the external integrated damping coefficient considering electromagnetic forces, f(w) is force of impact exerted by the flywheel on the magnetostrictive metal sheet, can be expressed as.

(11)

(11)

d is the impact coefficient, introduced to describe the impact force; r is the distance from the vertex to the centre of the flywheel.

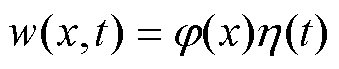

In this study, only the first vibration mode of the magnetostrictive metal sheet is investigated. The deflection can be expressed as

(12)

(12)

Where j(x) and h(t) are the mass normalized eigenfunction and the modal coordinate of the magnetostrictive metal sheet.

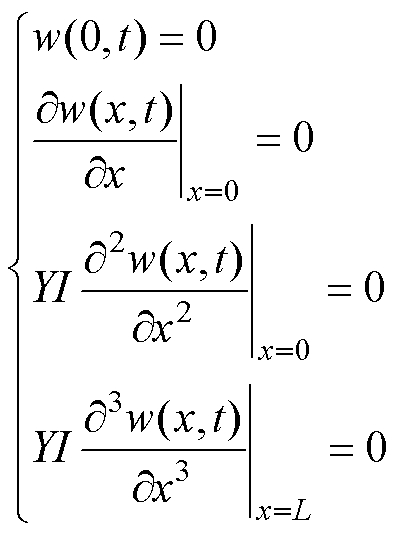

The magnetostrictive metal sheet is assumed to be proportionally damped, so that j(x) is the mass normalized eigenfunction determined by the undamped vibration equation and boundary conditions[17]. The boundary conditions are

(13)

(13)

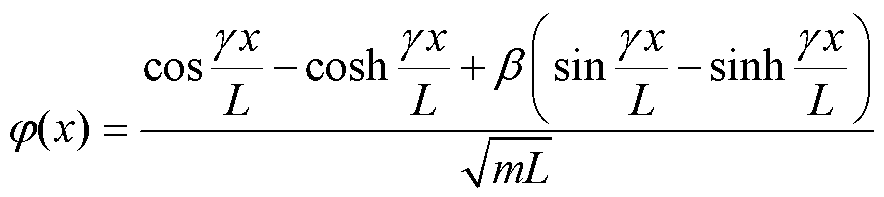

Therefore, the mass normalized eigenfunction is

(14)

(14)

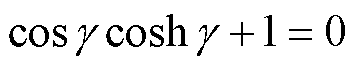

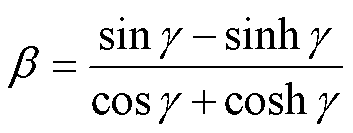

Where L is the length of the magnetostrictive metal sheet, and g satisfies the following relationship.

(15)

(15)

b can be expressed as

(16)

(16)

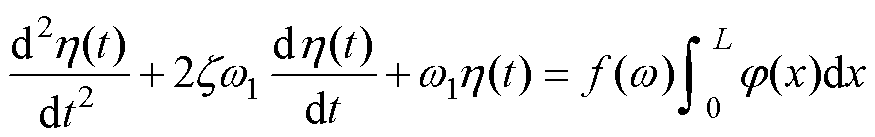

The vibration equation of the magnetostrictive metal sheet can be simplified to the ordinary differential equation.

(17)

(17)

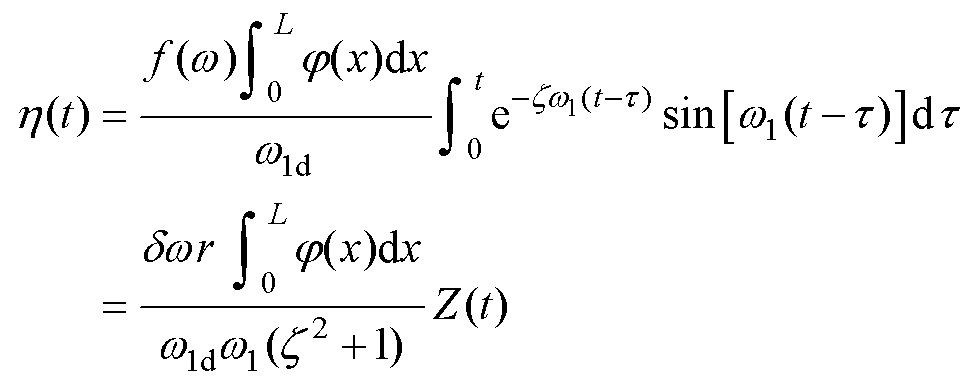

The modal coordinate h(t) is obtained as

(18)

(18)

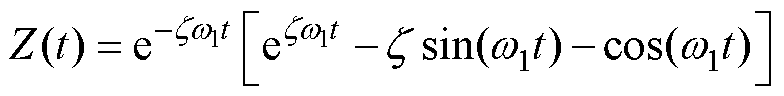

(19)

(19)

Where zisthe damping ratio, w1 and w1d are the undamped and damped natural angular frequency of the magnetostrictive metal sheet.

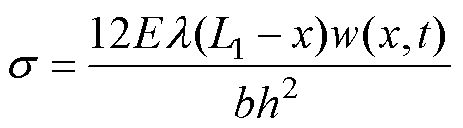

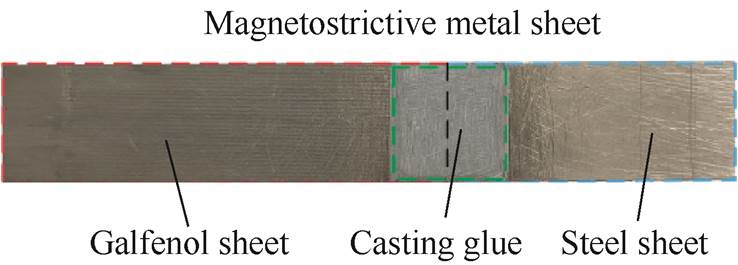

The stress on the Galfenol sheet is expressed as

(20)

(20)

where lis the cross-sectional moment of inertia, b andh are the width and thickness of the magnetostrictive metal sheet.

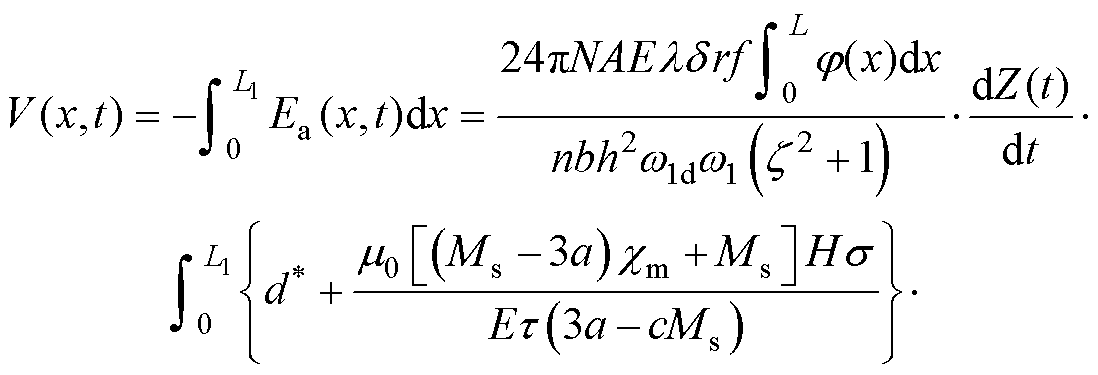

Combining Equ. (2), Equ. (8), Equ. (9), Equ. (12) and Equ. (20), the output voltage of the device can be obtained as

(21)

(21)

This model can simulate the output voltage at different excitation frequencies. Its applicable conditions are as follows:

(1) The bias magnetic field Hiis constant.

(2) The piezomagnetic coefficients dand d* are constants.

(3) Each part of the magnetostrictive metal sheet is uniform.

(4) Ignore the higher order vibration modes of the magnetostrictive metal sheet and only consider the first vibration mode.

Equ. (21) considers the stress distribution on the magnetostrictive metal sheet and the dynamic changes of the stress. It is a distributed dynamic output voltage model of the energy harvester with mechanical- magnetic-electrical coupling relationship of the Galfenol magnetostrictive material. When the structure and dimension of the energy harvester are given, increasing the excitation frequency f, the stress s and the magnetic field strength H will all lead to an increase in the output voltage.

As shown in the previous section, the output voltage of the harvester can be improved by increasing the frequency, stress, and magnetic field strength. Based on these three influencing factors, the structural parameter optimization design for the magnetostrictive structure, the rotating up-frequency structure and the bias magnet is carried out.

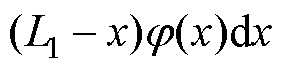

2.2.1 Mechanical structural Parameter Optimization Design

The toughness of Galfenol material is excellent, so in the process of vibration energy harvesting, there is no need to paste other materials on its surface to prevent it from breaking. As shown in Fig.5, the Galfenol sheet and the steel sheet are spliced into magnetostrictive metal sheet by using casting glue. The magnetostrictive metal sheet is designed to decrease the thickness of the Galfenol sheet and increase its length. This design increases the stress on the Galfenol sheet, as shown in Equ. (20).

Fig.5 Magnetostrictive metal sheet

It can be seen that the rotating up-frequency structure can convert low-frequency linear vibration into rotating high-frequency vibration, thereby increasing the excitation frequency. The UMVH is designed with a radius of the torsion bar of Rt= 5.3 mm, the thread angle of q =50°and the number of teeth of the flywheel of n=8. The UMVH can increase the excitation frequency to 16 Hz to 52 Hz.

2.2.2 MagneticStructural Parameter Optimization Design

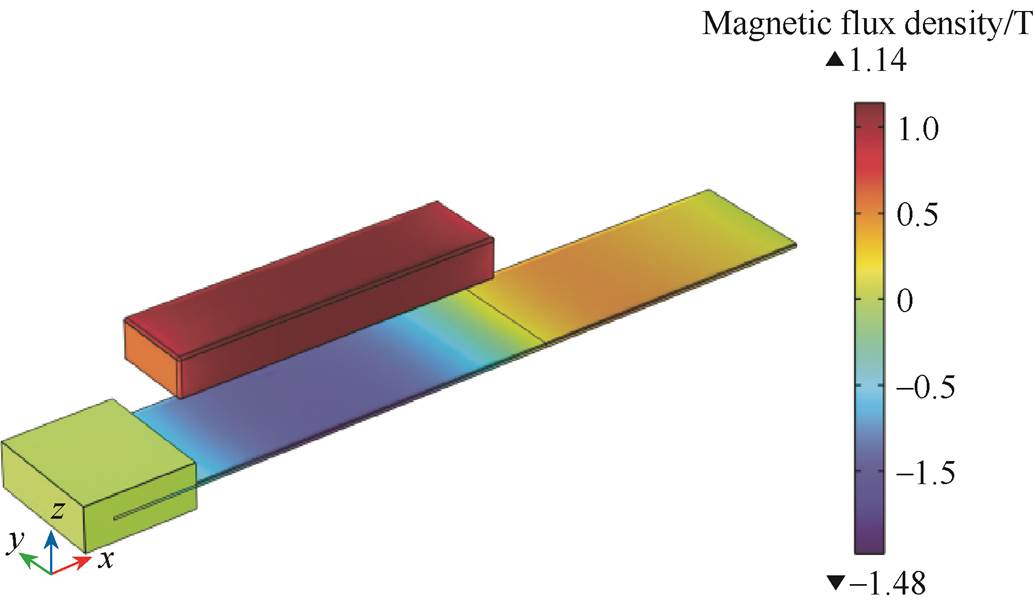

Achieving an appropriate bias magnetic field is crucial in increasing the output voltage of the vibration energy harvester. In order to obtain the ideal bias magnetic field, one should consider the size, position, and type of the bias magnet. This study selected a NdFeB magnet with dimension of 0.04 m× 0.01 m×0.005 m and its magnetization direction along the length. The bias magnet is placed horizontally on one side of the magnetostrictive metal sheet. Fig.6 illustrates the magnetic flux density distribution in the magnetostrictive metal sheet. The magnetic flux density is uniformly distributed along the width of the Galfenol sheet, ensuring that the Galfenol sheet was fully utilized.

Fig.6 The magnetic flux density distribution in the magnetostrictive metal sheet

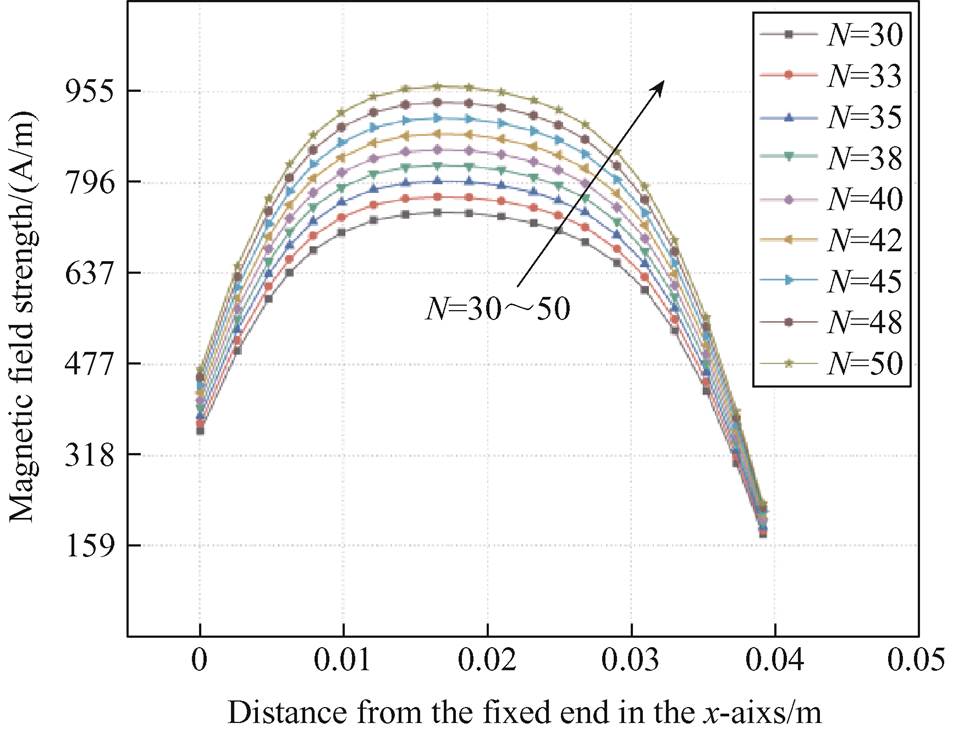

The saturation magnetic field strength of Galfenol ranges from 7.96 kA/m to 19.89 kA/m, and the saturation magnetic flux density is 1.5 T. The value of the saturation magnetic field of Galfenol depends on the applied pre-stress. In this device, the Galfenol sheet was not subjected to pre-stress, and its saturation magnetic field strength was 7.96 kA/m. When Galfenol is in the saturation state, the curve of the change in magnetic flux density with respect to stress tends to be horizontal, and the output voltage of the energy harvester is almost zero. Only when Galfenol is in the linear range close to saturation, the rate of change of magnetic flux density with respect to stress is significant[18], and the energy harvester can harvest considerable voltage.

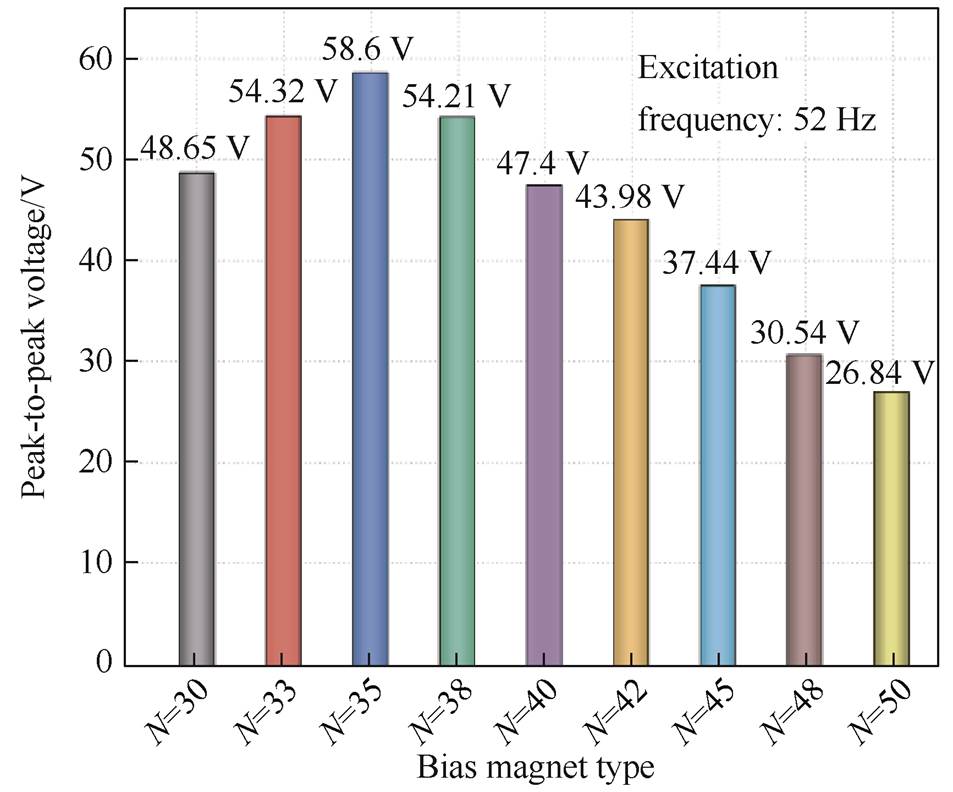

Different types of bias magnets are simulated in COMSOL to investigate their effect on the magnetic field strength in the Galfenol sheet. Fig.7 shows the distribution of the magnetic field strength along the x-axis in Galfenol sheet under different types of bias magnets. It can be seen that the bias magnetic field produced by the N=35 bias magnet is closest to saturation. Fig.8 shows the tested peak-to-peak voltage of the UMVH under different types of bias magnets. The experiment shows that selected N=35 bias magnet produces the best output voltage.

Fig.7 The magnetic field strength in the Galfenol sheet along the x-axis under different types of bias magnets

Fig.8 The tested peak-to-peak voltage of the UMVH under different types of bias magnets

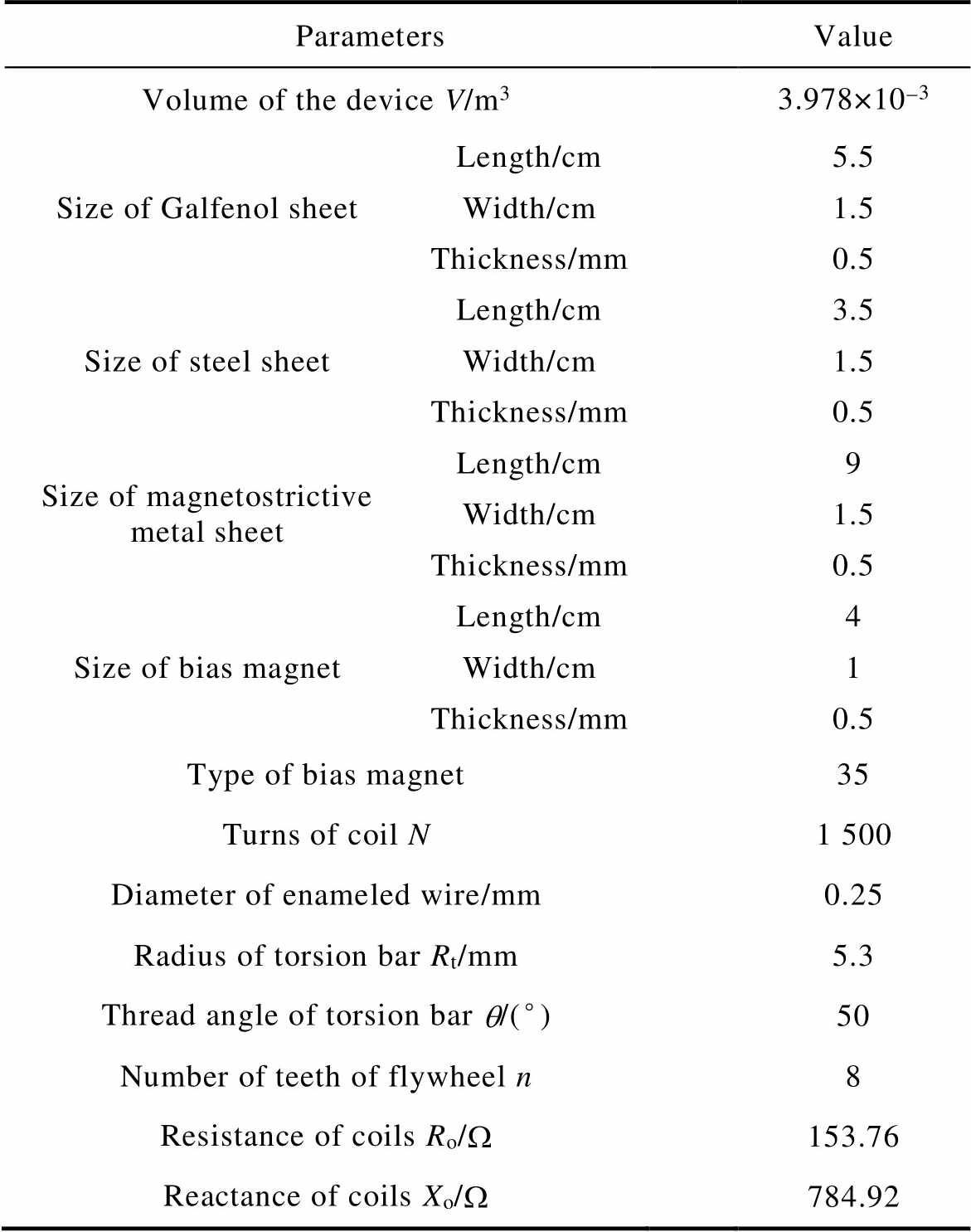

Through the mechanical-magnetic structural parameter optimization design, the detailed parameters of the UMVH are presented in Tab.1.

Tab.1 Values of parameters in the UMVH

ParametersValue Volume of the device V/m33.978×10-3 Size of Galfenol sheetLength/cm5.5 Width/cm1.5 Thickness/mm0.5 Size of steel sheetLength/cm3.5 Width/cm1.5 Thickness/mm0.5 Size of magnetostrictive metal sheetLength/cm9 Width/cm1.5 Thickness/mm0.5 Size of bias magnetLength/cm4 Width/cm1 Thickness/mm0.5 Type of bias magnet35 Turns ofcoil N1 500 Diameter of enameled wire/mm0.25 Radius of torsion bar Rt/mm5.3 Thread angle of torsion barq/(°)50 Number of teeth of flywheel n8 Resistance of coils Ro/W153.76 Reactance of coils Xo/W784.92

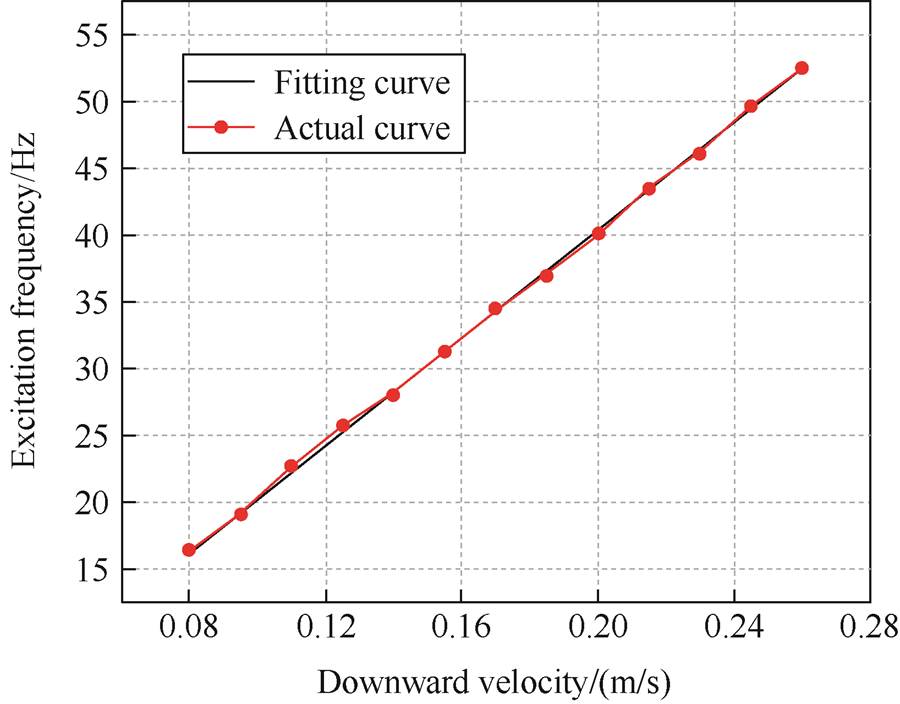

The frequency range of human walking is from 1 Hz to 2 Hz. The higher the walking frequency, the greater the velocity at which the footsteps on the cap[19-20]. Equ. (2) shows that the excitation frequency is proportional to the downward velocity v of the cap.

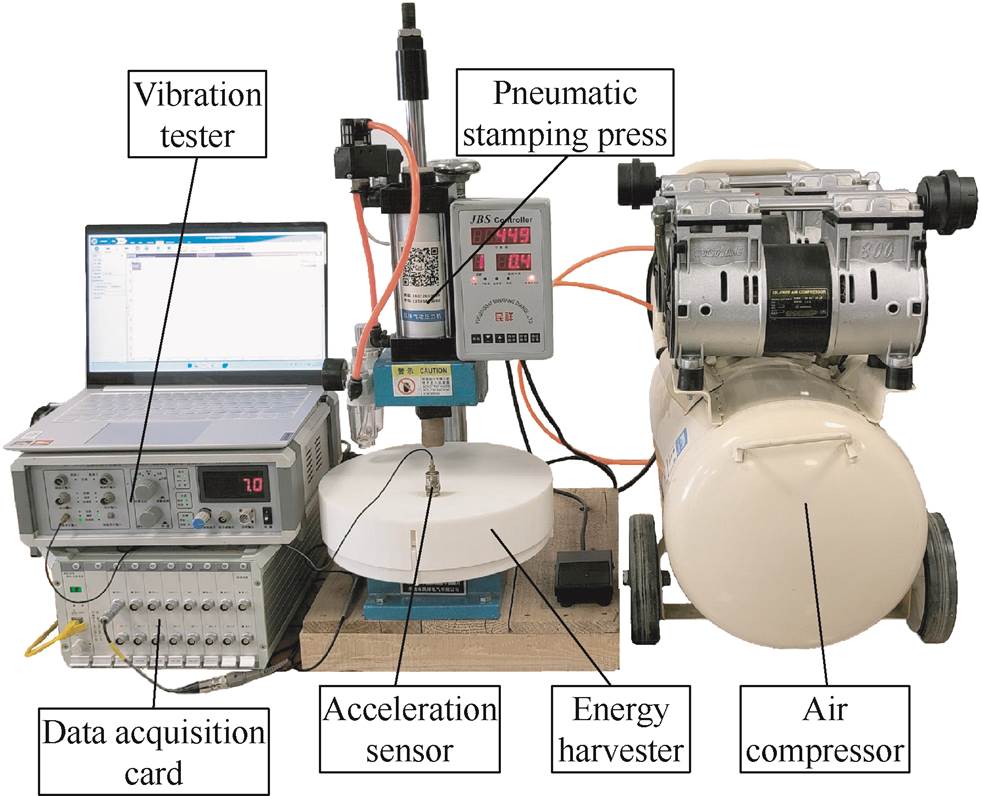

Fig.9 shows the block diagram of the working principle of the experimental system. The downward pressure of the pneumatic stamping press is used to simulate the foot stepping downward when walking. By adjusting the air pressure of the pneumatic stamping press, the velocity at which the cap downward can be controlled. Set the downward displacement to 15 mm by adjusting the nut on the top of the pneumatic stamping press. Fix the probe of the acceleration sensor on the surface of the cap to measure the acceleration of its downward. The acceleration sensor is connected to the vibration tester to transmit the acceleration data to the tester. The vibration tester then processes the acceleration data into downward velocity v. During the testing process, the data acquisition card will record the output voltage signal. Fig.10 shows the comprehensive experimental system.

Fig.9 Block diagram of the working principle of the experimental system

Fig.10 Comprehensive experimental system

The velocity of the downward pressure during the experiment was controlled within a range of 80 mm/s to 260 mm/s. Fig.11 illustrates the relationship between the downward velocity and the excitation frequency. The range of excitation frequency was found to be 16 Hz to 52 Hz.

Fig.11 Relationship between excitation frequency and the downward velocity

When the magnetostrictive metal sheet is plucked, it generates a free vibration and induces a voltage signal in the coil. Fig.12 shows the tested output voltage signals within one excitation cycle at excitation frequencies of 16 Hz, 28 Hz, 40 Hz, and 52 Hz. The output voltage signals exhibit an oscillation attenuation form.

Fig.12 The tested output voltage signals within one excitation cycle at excitation frequencies of 16 Hz, 28 Hz, 40 Hz, and 52 Hz

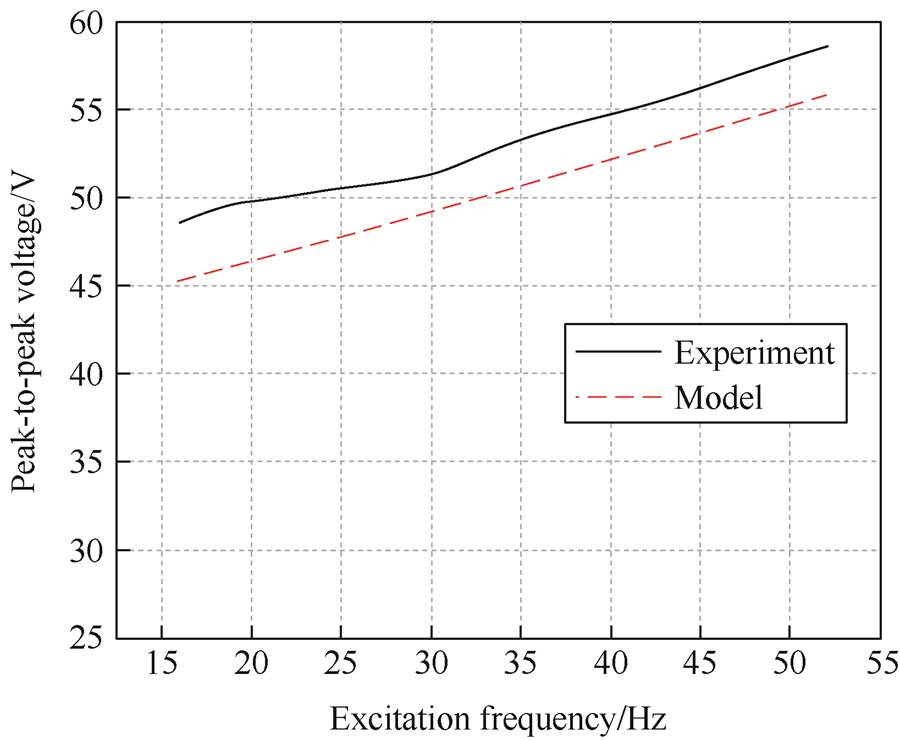

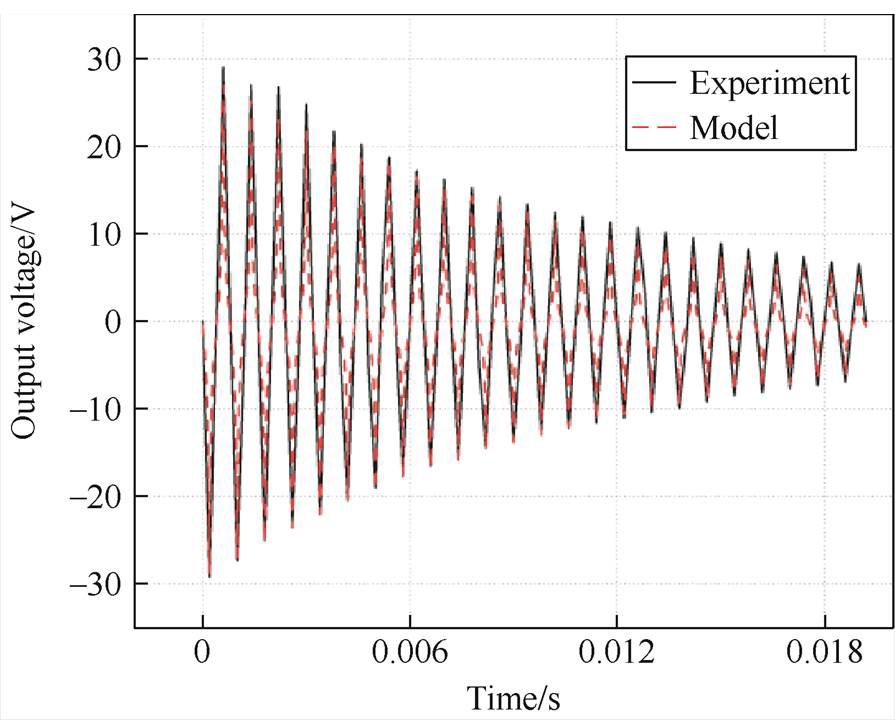

To investigate the voltage output characteristics of the UMVH, a comparative analysis is performed between the voltage output model and experimental data. Fig.13 shows the peak-to-peak voltage com- parison at different excitation frequencies under no- load condition. The average relative deviation is 4.9%. Fig.14 shows the output voltage signal comparison between the model calculation and the experimental test at excitation frequency of 52 Hz. It shows that the amplitude and attenuation speed of the two voltage signals are consistent. The average relative deviation is 8.2%. It indicates that the proposed dynamic output voltage model of the energy harvester can effectively predict the output characteristics under different excitation frequency conditions for harvesting vibration energy.

Fig.13 The peak-to-peak voltage comparison between the model calculation and the experimental test at different excitation frequencies under no-load condition

Fig.14 The output voltage signal comparison between the model calculation and the experimental test at excitation frequency of 52 Hz under no-load condition

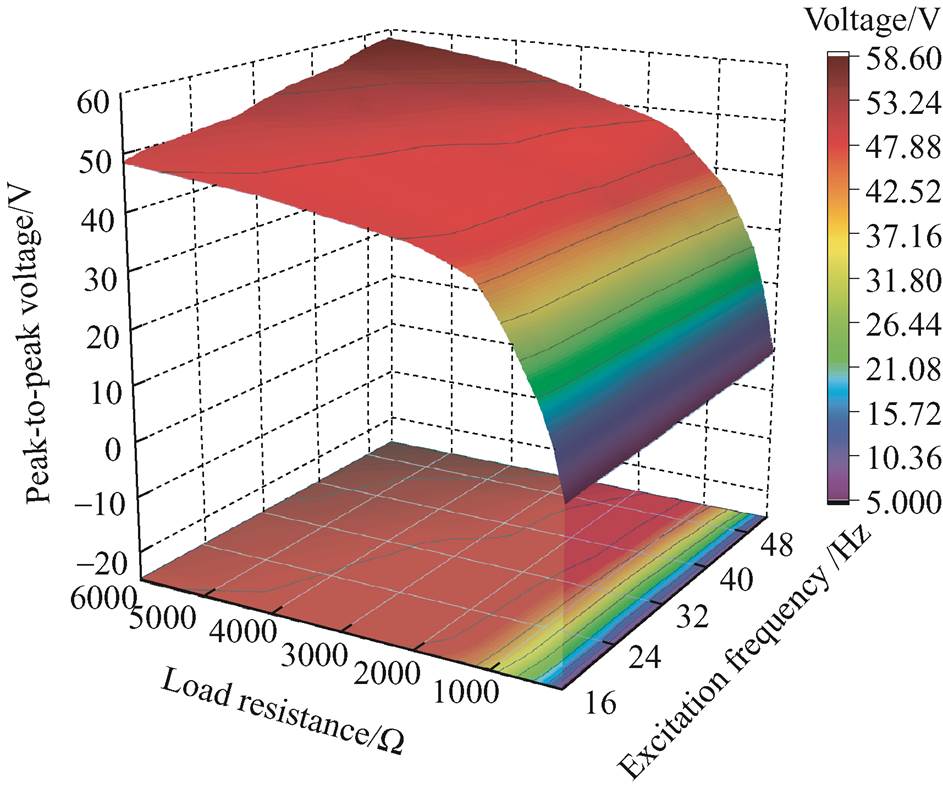

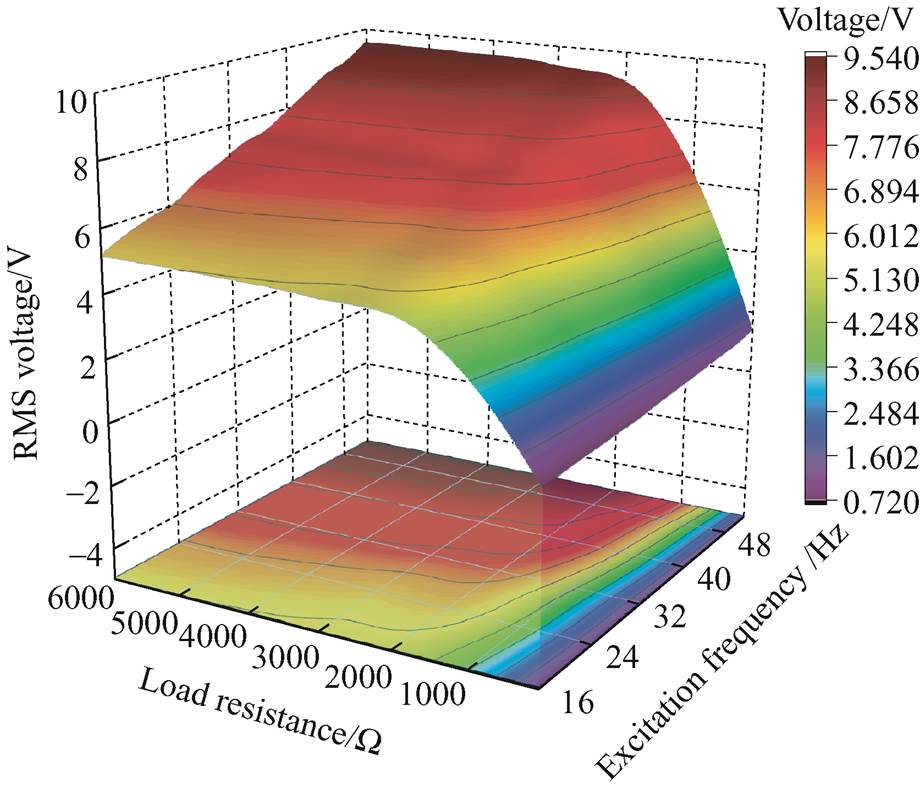

In order to study the output characteristics of the device under load, the peak-to-peak voltage, RMS voltage and RMS power under different loads were tested by experiments. Fig.15 shows the relationship between the tested peak-to-peak voltage and the load resistance at different excitation frequencies. Keeping the excitation frequency constant, the peak-to-peak voltage is positively correlated with the load resistance. Keeping the load resistance constant, as the excitation frequency increases, the peak-to-peak voltage tends to rise. The tested maximum peak-to-peak voltage is 58.60 V. Fig.16 shows the relationship between the tested RMS voltage and the load resistance at different excitation frequencies. The RMS voltage is positively correlated with both excitation frequency and load resistance. The tested maximum RMS voltage is 9.54 V.

Fig.15 The relationship between the tested peak-to-peak voltage and the load resistance at different excitation frequencies

Fig.16 The relationship between the tested RMS voltage and the load resistance at different excitation frequencies

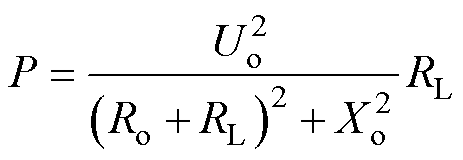

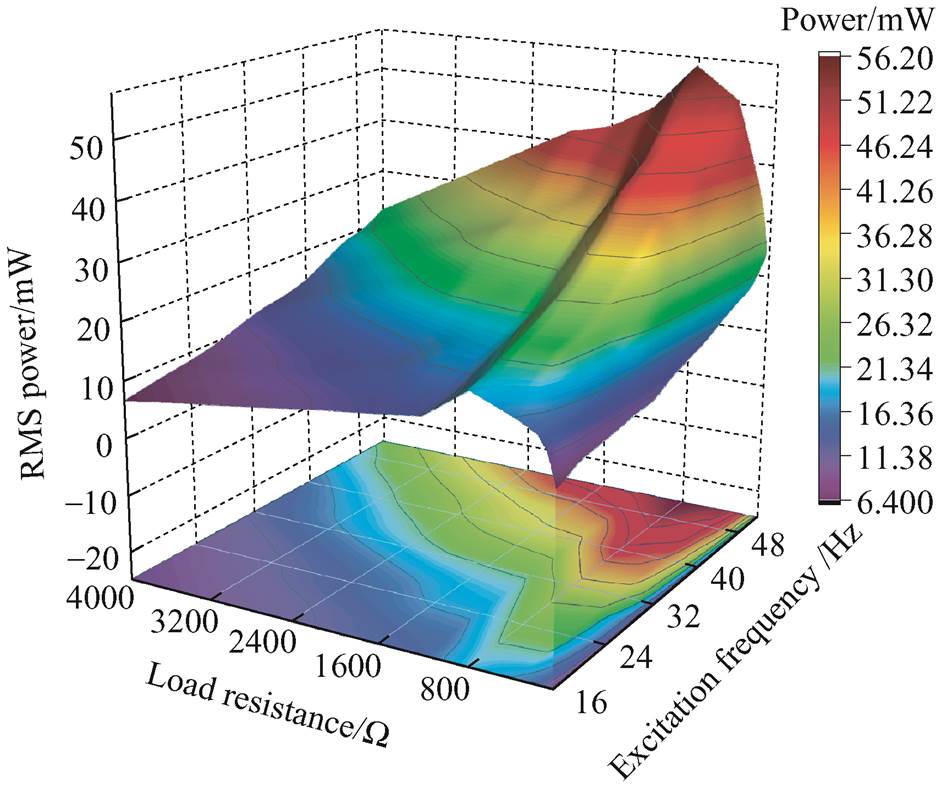

The RMS power P of the harvester can be expressed as

(22)

(22)

Where Uo is the open circuit voltage, RL is the load resistance, Ro is the coil resistance, Xo is the coil reactance. Due to the free vibration of the magnetostrictive metal sheet, when the walking frequency changes, the frequency of the output voltage is constant. This means that Xo is a fixed value. According to Equ. (22), the RMS power will vary with changes in load resistance. To achieve the maximum RMS power, the following conditions must be met

(23)

(23)

Substituting the values of Ro and Xo into Equ. (23), the maximum RMS power can be obtained. Fig.17 shows the relationship between the tested RMS power and the load resistance at different excitation frequencies. Keeping the load resistance constant, the RMS power is positively correlated with the excitation frequency. In the case of a load resistance of 800 W, no matter what the excitation frequency is, the RMS power at this excitation frequency is the largest. This demonstrates that the optimum load resistance of the UMVH remains constant as the excitation frequency varies, allowing the device to capture maximum power. It simplifies the impedance matching process.

Fig.17 The relationship between the tested RMS power and the load resistance at different excitation frequencies

A comparison is carried on between the proposed device and other vibration energy harvester with up- frequency structure in Tab.2. The working mechanism,vibration type, output voltage and output power are analyzed respectively. It can be seen that the proposed device has better performance with higher output voltage and higher output power when harvesting vibration energy from human walking.

Tab.2 Comparison between this work and previous vibration energy harvesters with up-frequency structure

ParametersThe harvester in Ref. [9]The harvester in Ref. [10]The harvester in Ref. [11]The harvester in Ref. [13]The harvester in Ref. [14]The proposed device Typeon-bodyon-bodyon-bodyoff-bodyoff-bodyoff-body Working mechanismEMEMPEPEMSMS Up-frequency√√√×√√ Free vibration×××√×√ Voltage/V1.75 (peak)2 (peak)9 (RMS)27.1 (peak)5.03 (peak)9.54 (RMS) Power/mW1.8 (peak)7.9 (RMS)13.88 (peak)1.24 (RMS)31.3 (peak)56.20 (RMS)

EM: Electromagnetic; PE: Piezoelectricity; MS: Magnetostriction; √: Yes; ×: No

A magnetostrictive vibration energy harvester with a rotating up-frequency structure is proposed. The rotating up-frequency structure converts the low- frequency vibration of human walking into high- frequency excitation vibration of the magnetostrictive structure. It also induces free vibration of the mag- netostrictive structure to keep the output voltage frequency constant, thereby simplifying the impe- dance matching process. This design ensures the UMVH produces good output characteristics with peak-to-peak voltage of 58.60 V, an RMS voltage of 9.54 V, and a RMS electrical power of 56.20 mW. A distributed dynamic output voltage model is established using mechanical-magnetic-electrical coupling model and Euler-Bernoulli beam theory. It can predict the dynamic output voltage at different excitation frequ- ency conditions. The model also provides a basis for the mechanical-magnetic structural parameter optimal design of the UMVH. Experimental results validated the accuracy of the output voltage modeland the mechanical-magnetic design. The UMVH can simul- taneously supply power to infrared sensors, sound sensors, smoke sensors and vibration sensors on the public place.

Reference

[1] 黄彦钦, 余浩, 尹钧毅, 等. 电力物联网数据传输方案: 现状与基于5G技术的展望[J]. 电工技术学报, 2021, 36(17): 3581-3593.

Huang Yanqin, Yu Hao, Yin Junyi, et al. Data transmission schemes of power internet of things: present and outlook based on 5G technology[J]. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society, 2021, 36(17): 3581-3593.

[2] 王红霞, 王波, 董旭柱, 等. 面向多源电力感知终端的异构多参量特征级融合: 融合模式、融合框架与场景验证[J]. 电工技术学报, 2021, 36(7): 1314- 1323.

Wang Hongxia, Wang Bo, Dong Xuzhu, et al. Heterogeneous multi-parameter feature-level fusion for multi-source power sensing terminals: fusion mode, fusion framework and application scenarios[J]. Transactions of China Electrotechnical Society, 2021, 36(7): 1314-1323.

[3] 高凯, 彭晗, 王劭菁, 等. 基于非对称弹簧的宽频率范围振动能量收集器[J]. 电工技术学报, 2023, 38(10): 2832-2840.

Gao Kai, Peng Han, Wang Shaojing, et al. Wide frequency range vibration energy harvester based on asymmetric springs[J]. Transactions of China Elec- trotechnical Society, 2023, 38(10): 2832-2840.

[4] 黄文美, 刘泽群, 郭万里, 等. 磁致伸缩振动能量收集器的全耦合非线性等效电路模型[J]. 电工技术学报, 2023, 38(15): 4076-4086.

Huang Wenmei, Liu Zequn, Guo Wanli, et al. Fully coupled nonlinear equivalent circuit model for magnetostrictive vibration energy harvester[J]. Transa- ctions of China Electrotechnical Society, 2023, 38(15): 4076-4086.

[5] 叶凯, 刘柱, 赵鹏博, 等. 一种基于磁通控制的电磁感应式磁场能量收集器功率提升方法[J]. 电工技术学报, 2023, 38(1): 37-46.

Ye Kai, Liu Zhu, Zhao Pengbo, et al. A power boosting method of electromagnetic induction magnetic field energy harvester based on magnetic flux control[J]. Transactions of China Electro- technical Society, 2023, 38(1): 37-46.

[6] Ylli K, Hoffmann D, Willmann A, et al. Energy harvesting from human motion: exploiting swing and shock excitations[J]. Smart Material Structures, 2015, 24(2): 025029.

[7] Suzuki Y. Recent progress in MEMS electret generator for energy harvesting[J]. IEEJ Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Engineering, 2011, 6(2): 101-111.

[8] Hasani M, Irani Rahaghi M. The optimization of an electromagnetic vibration energy harvester based on developed electromagnetic damping models[J]. Energy Conversion and Management, 2022, 254: 115271.

[9] Tan Qinxue, Fan Kangqi, Guo Jiyuan, et al. A cantilever-driven rotor for efficient vibration energy harvesting[J]. Energy, 2021, 235: 121326.

[10] Zhou Ning, Zhang Ying, Bowen C R, et al. A stacked electromagnetic energy harvester with frequency up-conversion for swing motion[J]. Applied Physics Letters, 2020, 117(16): 163904.

[11] Yin Zuozong, Gao Shiqiao, Jin Lei, et al. A shoe- mounted frequency up-converted piezoelectric energy harvester[J]. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2021, 318: 112530.

[12] Li Xin, Hu Guobiao, Guo Zhenkun, et al. Frequency up-conversion for vibration energy harvesting: a review[J]. Symmetry, 2022, 14(3): 631.

[13] Panthongsy P, Isarakorn D, Janphuang P, et al. Fabri- cation and evaluation of energy harvesting floor using piezoelectric frequency up-converting mechanism[J]. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, 2018, 279: 321- 330.

[14] Tan Yisong, Lu Guangpeng, Cong Moyue, et al. Gathering energy from ultra-low-frequency human walking using a double-frequency up-conversion harvester in public squares[J]. Energy Conversion and Management, 2020, 217: 112958.

[15] Meng Aihua, Yan Chun, Li Mingfan, et al. Modeling and experiments on Galfenol energy harvester[J]. Acta Mechanica Sinica, 2020, 36(3): 635-643.

[16] Erturk A, Inman D J. Piezoelectric energy harvesting[M]. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

[17] Erturk A, Inman D J. On mechanical modeling of cantilevered piezoelectric vibration energy harvesters[J]. Journal of Intelligent Material Systems and Structures, 2008, 19(11): 1311-1325.

[18] 黄文美, 陶铮, 郭萍萍, 等. 变压应力条件下铁镓合金棒材高频磁特性测试与模型构建[J]. 电工技术学报, 2023, 38(14): 3769-3778.

Huang Wenmei, Tao Zheng, Guo Pingping, et al. Analysis and modeling of high frequency magnetic properties of rod gallium iron alloy under variable compressive stress[J]. Transactions of China Elec- trotechnical Society, 2023, 38(14): 3769-3778.

[19] Deng Fang, Cai Yeyun, Fan Xinyu, et al. Pressure- type generator for harvesting mechanical energy from human gait[J]. Energy, 2019, 171: 785-794.

[20] Bertram J E, Ruina A. Multiple walking speed- frequency relations are predicted by constrained optimization[J]. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 2001, 209(4): 445-453.

摘要 传统的升频结构振动能量收集器在收集人体行走振动能量时存在输出电压低、有效功率低的问题。该文提出一种旋转升频结构磁致伸缩振动能量收集器。它由旋转升频结构、磁致伸缩结构、线圈和偏置磁铁组成。旋转升频结构能够同时引发磁致伸缩金属片的激励振动和自由振动。该设计将人体行走的低频振动转换为旋转的高频激励振动,同时简化了阻抗匹配过程。基于机-磁-电耦合关系建立了分布式动态模型来描述该能量收集器的输出电压。实验结果表明,该装置具有较好的输出特性,最大峰峰值电压为58.60 V,最大方均根电压为9.53 V,最大方均根功率为56.20 mW。

关键词:振动能量收集 磁致伸缩 旋转升频 动态模型 自由振动

中图分类号:TM619

Note brief

Huang Wenmei born in 1969, PhD, Professor, Major research interests include new magnetic materials, devices, and their control technology.

E-mail: huzwm@hebut.edu.cn (Corresponding author)

Xue Tianxiang born in 1997, Master's degree, Major research interests include new magnetic materials, devices, and their control technology.

E-mail: 2322866807@qq.com

DOI: 10.19595/j.cnki.1000-6753.tces.231946

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51777053, 52077052).

Received November 21, 2023;

Revised January 12, 2024.

(编辑 陈 诚)